- The Arrow

- Posts

- The Arrow #249

The Arrow #249

Greetings everone.

Let’s start off today with some poll responses.

Poll Responses, Emails, and Comments

WTF?

That’s what I always think when I get responses such as the next two.

The first one was merely an equational reply accompanied by a Totally Sucked grade on the newsletter. Here was the response.

Pregnancy= no drugs.

Does this mean I’m being castigated for writing that women shouldn’t take drugs during pregnancy? Or for saying they should? As I remember it, I don’t think I came down on one side or the other. I would tell my own pregnant patients to avoid drugs as much as possible, but if they were needed, and were safe for pregnant women, go ahead and take them.

The above response is stupid. If you’re going to write something like that, just go straight to the Totally Sucked grade and forget the comment. It’s meaningless. It doubtless means something to the respondent, but since I’m not able to read his/her mind, maybe a little explanation would be in order.

Here is the next one.

You continue to tout RFK which is hypocritical to your science background.

I’m not sure I’ve spent a lot of time touting RFK without explaining why I did so. Maybe I slipped some where, and if so, I’m sorry.

But like the previous commenter, your comment tells me nothing. I can assume that you are a total partisan, and that there is nothing RFK has ever done in his entire life that meets with your approval. There is plenty that he has done that meets with my approval and plenty he’s done that hasn’t. And I’ve mentioned what it was in all cases.

Why not just write ‘I disagree with your stand on RFK and vaccines, therefor I’m docking you a point in your polling grading (you actually docked me two, which is better than most who are partisan) but the rest of The Arrow was pretty good’ Unless you hated the entire thing, in which case why wouldn’t you just unsubscribe?

N=3

Last week I wrote about some of the readings MD and I got when we tried continuous glucose monitors for a month. What surprised us the most was the reading we got when we ate steel cut oats. The ones shown below, specifically.

We cooked the oats in water, and when fully cooked we ate them with a couple of pats of butter and a little half & half. No sugar, no fruit, no nothing else.

Our blood sugars zoom up to over 130 mg/dl or so and stayed there for at least a couple of hours. We were both stunned. Nothing in our one-month experiment had responded anyway like that. Even sushi rice, notorious for running up blood sugar, went up quickly, then back down quickly. And I can’t remember how high sushi rice drove our blood sugars up, but it wasn’t far off from the steel cut oats. It just didn’t stay up as long.

I heard from another poll respondent, who tried the same (I think) steel cut oats.

About that oatmeal, I started having that same high quality oatmeal for breakfast every day about 8 months ago. Well, surprise -- when I went for my annual blood tests, for the first time in my 87 years, my A1C was 5.7. I was so shocked that I immediately stopped oatmeal and bread and all other carbs that could be suspect. In 3 months, I will have new lab work to see what changes there night be. I'm so glad you mentioned the oatmeal because that is really the only thing that had changed in my regular diet. But, dang, it was so good! Anyway, thank you for all you do.

So, beware of the steel cut oats. And let me know if you’ve tried other brands and found different responses.

If you would like to support my work, take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Moving on to other things…

I maintain a subscription to the New York Time primarily because it allows me to provide you, reader of the Arrow, free, full-text articles that it hides behind paywalls for everyone else. I don’t spend a lot of time reading the Times, however, because it is so blatantly partisan. I had a little time on my hands a couple of days ago, so I pulled up the website and made a quick run through of the titles to see if anything caught me interest.

Sure enough, there was an opinion piece titled “Why Young Men Are Losing Faith in Science,” written by a professor of astrophysics at the University of Rochester.

The article starts out with the professor on a plane next to a 20-something young man who, in noticing the book the prof was reading on astrophysics, asks if he is a scientist. The prof answers in the affirmative, and the young man starts regaling him about how much he loves science and talks about all the ‘scientific’ shows he watches on TV.

He listened to podcasts like “The Joe Rogan Experience” and others where scientists came on as guests and talked about quantum mechanics, black holes and ancient aliens.

Encouraged by his enthusiasm, I told him that not everything on those shows was science (case in point: ancient aliens). I advised him to be on his guard. Then, with all earnestness, he told me while I was clearly OK, it was common knowledge that sometimes, on some subjects, science hid the truth.

After 30 years as a researcher, science communicator and university science teacher, I’ve been unsettled by what appears to be a growing skepticism of science among some of my Generation Z students, shaped in part by the different online cultures these young people have grown up in. While I cannot speak to what happens in every corner of the internet, I can speak to the one I’ve been invited into: the “manosphere” — a loose network of podcasts, YouTubers and other male influencers. I’ve appeared on some of the manosphere’s most popular shows, including Joe Rogan’s. I’ve watched how curiosity about science can slide into conspiracy-tinged mazes rooted in misinformation. And I believe the first step out of the maze for young men begins by reasserting to them the virtue of hard work — an often grueling but indispensable part of finding the right answers in science. [My bold]

Then follows this paragraph:

The implication, of course, is that “reservations about new vaccines” is anti-science.

The jerk writing this piece may have been on the Joe Rogan show, but as an astrophysicist he doesn’t know any more about vaccines—new or old—than William F. Buckley. And William F. Buckley is dead.

Who knows? The Times may have inserted that, or required that he write it. Had he written it 30 years ago when the Times was the Times, the editor would have made him provide some basis for making the claim. But today’s Times is different. As A.J. Liebling, whom I was turned onto by my friend Gary Taubes, wrote: “The function of the press in society is to inform, but its role in society is to make money."

Instead of reporting the news, however it falls, the Times reports what its readers want to read.

Fortunately, I did’t let this interaction with a typical Times writer drive me away. I kept on reading and came across a long, sad, article that reminded me of one of my own experiences. In reminding me of my own experience, I think we can probably all profit from a deep dive on a tragedy.

Two Tragic Cases. One in NY and One of My Own

A New York Tragedy

This is a nightmare case for anyone, especially a parent. And it is the kind of in-depth article the NY Times is known for. Or at least used to be.

Here are the brief essentials of the case as reported in the Times.

A 20-year-old college student goes to a soccer game at Yankee Stadium. On the subway ride there, he told friends he felt lousy. After the game, he felt even worse, so he went to the emergency room. He was evaluated and given the diagnosis of “acute viral syndrome” and sent home. The next day, he felt even worse.

He went back to the ER with a friend, this time reporting headache and chills and was again examined and discharged with a diagnosis of “acute viral syndrome” and instructions to take Tylenol and Zofran (I’m assuming for his nausea.) Before being discharged, he was checked for meningitis, flu, and respiratory syncytial virus, all of which were negative. He went back to his dorm room and two days later he was dead.

Two years after Sam’s [the young victim’s name was Sam Terblanche] death, his father (who is known as “VT”), still can’t understand how his 20-year-old son could have sought help at the Mount Sinai Morningside emergency department twice in 24 hours then died alone in his dorm room two days later.

Terblanche met with the chief medical officer, Tracy Breen (who has since become the hospital’s president), two months after Sam died. He made a recording of the meeting and handed it over as part of pretrial discovery. In a well-lit room, seated at a conference table, Breen explained that after an internal review, Mount Sinai Morningside had concluded that it was “comfortable, satisfied, whatever totally non-helpful word we use” with its decision to discharge Sam from the E.R. It was a “gut punch,” Terblanche told me.

Breen conceded that Sam’s death was an emergency provider’s “worst nightmare” and would likely prompt staff to “wonder and feel, like ‘Did I get it wrong?’” At the same time, she informed Terblanche that the details of the review were off limits to him — “confidential and internal.”

Terblanche has been a lawyer his whole professional life, and he sees that meeting as a turning point. How can an executive acknowledge that the best doctors sometimes err while also insisting, without providing evidence, that the hospital was blameless? From that moment, he realized that if he wanted answers, he would have to fight. In August 2024, he sued Mount Sinai Morningside and five doctors who work there for medical malpractice and wrongful death. In a statement, Mount Sinai expressed sympathy for the Terblanche family but declined to comment on Sam’s case.

“Any patient loss profoundly affects not only families, but also the care teams who dedicate themselves to providing the highest quality care,” the statement said.

The article includes a number of statements from ER physicians as to the purpose of an emergency room. Many people these days use it as a primary physician. According to the article a “third of Americans have no primary care physician, up from a quarter 10 years ago.”

When I was doing ER work long before ten hears ago, most of the patients I saw had minor illnesses that could have been taken care of in any doctors’ office, but they came to the ER because they couldn’t get an appointment with their regular doctor.

I don’t know how it works now on the front lines, but back then ER physicians worked 24 hour shifts as the only doctor in the ER. Usually shifts started at 6 am and ended at 6 am the next day. I can tell you it’s frustrating when it’s 2:30 am, you’ve just dealt with a gunshot wound and a heart attack, and you finally hit your little call-room bed for some well-needed shut eye when the nurse rings you to tell you there is a patient who just came in with a sore throat he’s had for three days.

My frustration with ER work is what led MD and me to start the first urgent care center in Arkansas. I had reckoned that about 90 percent of the patients coming into the ER I worked in did not have emergencies. The were sick or injured and couldn’t get in to see their doctors. When we opened our first facility—which was not called an urgent care center then, but a free-standing emergency clinic—we figured the docs in town would be happy. Instead, they were pissed and accused us of trying to steal their patients by having a walk-in clinic.

How times have changed. Now there is an urgent care center on every corner it seems.

In the time I spent working in actual ERs, I noticed there were two broad categories of ER docs: Those who thought they were primary care docs and there just available in case an emergency came through the door; and those who thought ERs were for emergencies only and anyone else shouldn’t be there. I started out as the former, and ended up as the latter. It was a good thing the urgent care idea occurred to us, because I was getting pretty burnt out.

I wasn’t nearly as bad as a friend of mine I went through med school with. He had gotten sued early in his career over a business deal—not medical malpractice—and it cost him a lot of money and had a major impact on his thinking.

He came to the conclusion that his job was not to be sued for malpractice. He once told me that when patients came into his ER, all he focused on was anything that could be life-threatening, or that could get him sued. If he found nothing that fit those particular bills, he “Motrinized” the patients in question and sent them packing. (For those who don’t recall, Motrin was the first trade name of ibuprofen, now better known as Advil.)

Which leads us back to the sad story of the young man who died.

When I read the article, it looked to me like the ER docs did a pretty good job. I would have probably gotten a chest X-ray (but it would have depended upon whether I thought the patient needed it). Other than that, I would have treated him pretty much the same way.

At this ER (and probably at all ERs now), there was a system that if a certain combination of signs and symptoms were entered (we had no computers when I was doing ER work, only paper charts, so it wouldn’t have worked anyway), certain serious conditions would pop up reminding the busy doctor(s) of something they may have over looked. In the case of this young man, it popped up warning the docs to be alert to sepsis.

Sepsis is an incredibly dangerous condition in which a patient can go from feeling kind of crappy to being dead in a matter of hours. It should always be front of mind in anyone working in an ER. But most docs are always thinking about it, because it is so deadly and disastrous. And there is very little time to do anything about it once it becomes obvious.

According to the CDC, sepsis is a life-threatening condition in which the body has an extreme, dysregulated response to an infection, resulting in organ dysfunction and potentially rapid deterioration or death if not promptly treated.

Usually it is associated with a bacterial infection, but it can be caused by a virus, a fungus, or even a parasite. But by far and away, the most common cause is a bacterial infection. All of these infections—bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic—have classic presentations, but they don’t always follow the rules.

Bacterial infections usually start out and become progressively worse. Viral infections, on the other hand, often wax and wane. You can feel like crap one minute, and 30 minutes later feel like you’re a whole lot better. When you really aren’t. And it goes back and forth.

It takes some judgment on the part of the treating physician to sort all of it out. And from my reading of the article, it looks like the docs did a pretty good job of it. As I read, I kept waiting for the announcement that the blood work came back after the kid had died and showed sepsis. But it didn’t. In fact, all the blood work done came back showing really nothing that should have killed this young man.

The father—a lawyer—is suing everyone involved for missing the diagnosis of sepsis. But I don’t think the young man had sepsis. The family will probably win, because juries don’t look at the situation as they should. There was no sepsis. They feel sorry for the family and figure they need the money to compensate for their loss whether or not the hospital and doctors were responsible. The hospitals have big pockets, which is why malpractice insurance keeps going up and up for doctors, which means fees keep going up. And docs keep retiring.

My Story

One early evening I was working—as the only doc—in a really busy ER in Little Rock. All the normal ER stuff was coming through, and I had every exam room filled.

The nurse told me she had just put a patient in the last available room. I asked what the problem was, and she said the patient was a “pretty sick puppy.”

I stuck my head in the door just to quickly assess the situation before leaving him for the hour or so it would take me to go through all the other patients sequentially before getting to him.

It was kind of a weird scenario. The patient, who appeared to be in his forties, was on the exam table in some obvious discomfort. A woman and a man of the same age were in the room with him. I asked the patient about his symptoms, and he just told me he just came down with something that afternoon and felt terrible. I couldn’t elicit any specific symptoms from him. He did have a temp of 101F, but all other vital signs were okay.

What was bizarre—to me, at least—was the two other adults in the room. The woman, who said she was his wife, was joking around with the other man, not taking the patient’s situation seriously at all.

One skill a physician really needs is to be able to tell if a patient is critically sick. And I’m pretty good at that. Or at least was. I don’t know if it’s learned or innate, but wherever it came from, I have it. I had no idea what was specifically wrong with the patient I was dealing with, but I knew he was very ill. And I mean deathly ill.

I ordered a bunch of labwork on him, and while I was waiting for it to come back, I got caught up on all my other patients. During that time, I kept ducking my head in the door checking on my very ill patient. Who wasn’t getting any better. If anything, he was getting worse. And his wife and friend kept acting like they were at a party.

Once all the labwork was in, there was no ‘there’ there. He had elevated lymphocytes, which are a sign (but not a 100 percent one) of a viral infection. His leukocytes were low normal—leukocytes usually go screaming up with a bacterial infection. His sedimentation rate was really high. A sed rate is a non-specific test that’s not used much anymore (and wasn’t in fact used much back then), but if elevated, it is an absolute indicator something bad is going on, though it doesn’t tell you much specific.

Thanks to his elevated sed rate, I knew something was going on. I just didn’t know what.

I told his wife that he was very ill. “Low sick” were the words I used. She repeated “low sick, what do you mean?” I told here he could very easily die. I don’t think she much believed me.

I did what the doctors of the young man in the Times article didn’t do. I admitted him to the hospital. I’m not faulting the docs who took care of the kid who died; I don’t have any idea how the young man looked. But if he looked anything like my patient, I would have admitted him.

I did order a chest X-ray to be taken as part of his admission orders. It was normal.

In admitting this patient into the hospital, I transferred his care from me to the physician who was to take care of him. This isn’t any brush off of responsibility. I had no admission privileges. I worked a few shifts a week in the ER, but I didn’t have a clinic at the time or the ability to admit unless I admitted under a specific doctor. In this case, the doctor on call for internal medicine.

The next day, I called him. I wanted to see how the patient was doing and what his diagnosis was. The doc told me the patient had died that morning. And that he had no diagnosis. All his labwork came up pretty clean. The diagnosis of death was acute viral syndrome.

I told him how the wife and friend were acting totally inappropriately while in the ER exam room with the patient and me and suggested he might want to check some toxicology just to be sure. I was concerned because I thought the two of them might be having an affair and perhaps poisoned him to get him out of the picture. The physician taking care of him assured me that the wife was devastated and had no idea how ill he was, although I’d tried to forewarn her.

What happened to these two patients to bring about their relatively sudden deaths when they were both young and healthy?

I had no idea on my own patient, though I have thought of him many times in the intervening years. I got a brief hint of what may be behind many of these deaths when I thought about a couple of patients I wrote about in previous issues of the Arrow, which I can’t search. The Wall Street Journal wrote about these two patients five or six years ago, but I can’t search the WSJ for any articles prior to four years ago. However, I did find an article from the BBC on the Texas teacher. I couldn’t find anything about the other patient the WSJ wrote about, but I remember the victim. She was a little girl about ten years old who came down with the flu and died. Her dad was a doctor. And prior to getting the flu, she was a healthy child. What happened?

My Speculation on Cause

I’ve wondered about these cases a long time, and I think I might have an idea as to what happened. This is sheer speculation on my part, but it is scientific sheer speculation born of all my readings over the past five years about viruses and vaccines. Had Covid never darkened our door, I would never have even had this speculation.

It is a well known fact that over time viruses mutate into less virulent and more infectious forms. Viruses, like all living things (though whether viruses are living is a philosophical question) want to survive and reproduce. If they kill their host, they die, too. Which is why the mutations that provide the greatest chance for the most viral reproduction are to become less severe and more infectious.

We saw this in spades with the Omicron variant of Covid. Compared to the original version of Covid, the Omicron version was vastly more infective, and less deadly. MD and I were traveling all over the place during the early Covid days and never got it. In fact, we were part of an antibody surveillance study at the University of Texas medical school requiring us to come in for periodic blood draws to see if we had been infected. Both of us thought we had been infected early on, because we had symptoms attributed to Covid in December 2020 following a trip to Hawaii just before it hit in earnest. But the blood samples proved us wrong.

In January 2022, when the Omicron variant was loose, we both got it within a couple of days of one another. And our entire family (in two different states) got it around the same time. MD was sick for a couple of days. I had a fever and some fatigue for two nights and one day, then I was fine. When we went in for our blood draws, we had antibodies to both the spike protein and the nucleocapsid, meaning we were infected with the real virus, not the vaccine. Which we hadn’t taken anyway.

When viruses mutate, they are not designed by nature to mutate into a less virulent more infectious form. That’s just one of the many ways in which viruses mutate. They mutate in all directions. Some mutate into more virulent forms. But those incredibly virulent forms don’t survive long to reproduce as they kill their host and die with it.

What if the young man in New York, the two people the WSJ wrote about, and my guy in the ER died from an unusual viral mutation that was not more benign as expected, but terribly more virulent? All of the symptoms of a viral infection would be present, but some killer mutation would wipe out the patient without really leaving its tracks.

This segment ran on longer than I intended, but I wanted to flesh out my argument. And when I got started, I couldn’t stop. It basically used up most of the space the platform allows for The Arrow. If you enjoyed it, thanks for the indulgence. If not, I’ll be back to regular fare next week. Meanwhile, take a look at Arby’s newest offering.

On NBS Patrol

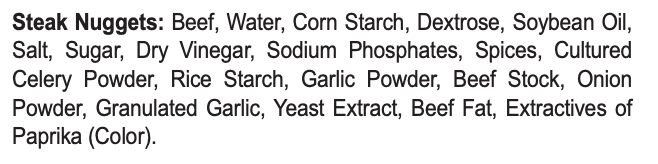

On the NBS front, I wanted to alert you that Arby's launched a new menu offering called Steak Nuggets. They're advertised and reviewed as being not breaded (like chicken nuggets one supposes) but rather just beef, seared, smoked, and seasoned. And even gluten free. And said by reviewers to taste something like burnt ends of barbecued brisket, which is shorthand for 'delicious and savory' to a barbecued meat lover.

Arby’s Steak Nuggets

And it all sounds nutritious and healthful. Just ‘the meats’, as they say at Arby’s.

But is that so? A quick look at the ingredients list tells the sad truth.

It's true as advertised that these bites aren't breaded on the outside in the traditional sense, but I’d say they’re rather 'breaded' on the sly. Lurking within that ‘ingredient’ that they just refer to in the review description as 'seasoning' (it’s just beef, seared, smoked, and ‘seasoned') are all the carbs and BS additives you’d expect (apart from enriched wheat flour, I guess, that would normally be in breading) designed to give their nuggets the desired savory mouthfeel and add sweetness to the barbecued flavor imparted by the extracts of paprika they say is for color. There’s cornstarch, dextrose, sugar, and rice starch, not to mention soybean oil and sodium phosphates. And rice starch, at least in our n=2 was one thing that really ran the CGM up. Caveat emptor!

The Bride and I won't be lured in, tasty and meaty though they appear.

Odds and Ends

$1million in gold and silver coins found in 310 year old shipwrecks off the coast of Florida. Gets my treasure hunting blood up!

We (MD especially) love seeing ancient human personal artifacts. Particularly mundane objects that are ornamented and made beautiful when all they really need to be is functional -- a comb, a bowl, or cup. That human drive to make something pretty for no reason other than beauty is its own reward is marvelous. Like this 13th Century Scottish hair pick carved from local red deer antler.

Shackleton's expedition to the South Pole has long fascinated me. How did they survive the month's long return? Endurance, of course -- OK bad pun, sorry. Here's a video that explains it.

And if you're a fan of good Scotch Whisky, it may interest you to know that aboard Endurance bound for the South Pole were cases of whisky -- The Old Mackinlay's recipe—maybe part of that survival explanation. (That name was especially interesting to me because that's my maternal Scottish clan, McKinley.) Some cases were discovered beneath their polar outpost a while back, still wrapped in straw in their wooden cases. The bottles were carefully harvested and sent first to New Zealand to be thawed and then shipped to a master distiller in Scotland to be reverse engineered. Which was done. And a really tasty whisky called Shackleton is the result. Take a look whisky fans. (And no, I’m not an affiliate. Just a fan.)

After stone tools and fire, what's early humankind's next most important invention/discovery?

Is there an upper limit on number of friends? Apparently the brain maxes out being able to handle more buds and pals, but at a level much higher than I would have imagined, or else how they define 'friends' differs from my own. I’ve lots of acquaintances but not nearly so many true friends by a sight.

Goin' like a house afire! Cool to look at and very creative, but I'm still not sure it isn't a real life equivalent of crying FIRE in a crowded theater. Although as a former firefighter, it's just the kind of fire I'd be relieved to roll up on.

The most profitable songs in music history. Some I’ve never heard of. Some surprised me. But the number one, worth about $70 million in lifetime revenue is all too familiar, and I’m sure you know every word by heart.

Why do cats meow at humans and not at each other? I'm so intensely allergic to cat dander that I try not to touch them with a double-10-foot pole, all except one little Bengal Cat belonging to a friend of ours, which is, as advertised, truly hypoallergenic. I can pet her without reaction, and I can attest she does try to converse.

IRS furloughs nearly half of its workforce due to government shutdown. Good news, I guess, if you’re worried about an upcoming audit.

Years too late, after many ruined careers, Boris Johnson admits Net Zero is unworkable, and he “got carried away.”

Amazon is putting prescription drugs into vending machines at its One Medical clinics, starting in LA, so patients can pick up their medicine on the way out of appointments with doctors. Pretty soon there will be messages saying, Sorry, there has been a delay with your prescription. It will now be available here next Thursday.

The 20 international foods most commonly mispronounced by Americans.

On today’s date, in 1936, the Hoover Dam began transmitting electricity 266 miles to Los Angeles.

Which state is the #1 in pumpkin growing? It grows three times the pumpkins than the state that comes in second. You’ll probably be surprised. I was.

Primeval star may be the most ‘pristine’ object ever discovered in the universe.

He was expected to get Alzheimer’s 25 years ago. Why hasn’t he?

Video of the Week

This compilation of the 80 most iconic guitar intros (since the 1930s at least) as ranked by Netherland’s guitarist Paul Davids (music degree from the Rotterdam Conservatory) is nothing short of a heady stroll down modern blues/jazz/pop/rock memory lane. It will take you back (if you’re vintage like the Bride and I) and introduce you to a whole batch of newer riffs you likely don’t know (unless your Millennial or Gen Z). And he does it all in a single take, from memory, which speaks to his guitar plucking cred. I love some of them, don’t agree with them all. Curiously he left out a few of my favorites intros: Stairway to Heaven, Layla, and Hotel California, but different strokes and all. Dust off your axe and play along!

Time for the poll, so you can grade my performance this week.

How did I do on this week's Arrow? |

That’s about it for this week. Keep in good cheer, and I’ll be back next Thursday.

Please help me out by clicking the Like button, assuming, of course, that you like it.

This newsletter is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end. Really, thanks. If you got something out of it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber if you aren’t yet. I would really appreciate it.

Finally, don’t forget to take a look at what our kind sponsors have to offer. Dry Farm Wines, HLTH Code, Precision Health Reports, and Jaquish Biomedical.

And don’t forget my newest affiliate sponsor Lumen. Highly recommended to determine whether you’re burning fat or burning carbs.

Reply