- The Arrow

- Posts

- #252 Nutrient Partitioning

#252 Nutrient Partitioning

Greetings everyone.

All I can say is that I hope your week has gone better than mine. I’ve been deeply mired in the shittification of everything. I won’t bore you with the details (except for one—which someone out there might be able to help me with), but I’ve had an email account compromised, received a bill from 2017 from the IRS, got screwed by DirecTV, had the power go out for hours, and, worst of all, had ~$2,300 stolen from my PayPal account.

Someone notified me he had just sent me a PayPal payment and asked me to check if it came in. I checked; it had. Maybe 15 minutes later, I went back to PayPal to move funds to my bank account and found my balance to be $0.

Then the nightmare began. I was trying to communicate through a bot, which was the only choice I had. I spent hours on multiple occasions going back and forth. Finally, I got a message that told me my time had expired and kicked me out of PayPal.

Whoever took the money did it in three transactions, each under $1,000, but all three different numbers. I tried to send the PayPal bots the amounts of the three transactions, but they took only one and gave me a reference number without the amount stolen attached. Then I asked them about the other two, and got absolutely nowhere. I still don’t know which one of the three they are investigating. They said they would give me a resolution by Nov 4.

If any readers out there work for PayPal or have any insight as to how I could deal with this—secret phone numbers to get me to a human, whatever—I would appreciate it.

If you would like to support my work, take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Metabolic Nutrient Partitioning

Fat Zucker Rat courtesy Wikipedia

The CICO theory of weight management seems so simple that most people take it as gospel. I mean think about it: If you eat more, you gain weight. If you cut back, you lose weight. Easy peasy.

But you know what H.L. Mencken said about simple solutions.

For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.

Another quote I put up a week or so ago is also germane to the question.

It doesn't matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn't matter how smart you are. If it doesn't agree with experiment, it's wrong.

I have a friend who insists CICO works like a charm. Female models, he says, gain a few pounds, then cut their calories a week before a shoot, and they lose all their excess weight. Every. Single. Time. Without Exception.

He also says the same about bodybuilders. When they are getting ready for a competition, they work to build muscle, then the last couple of weeks, they cut the calories and shed their subcutaneous fat, giving them the sharp definition required. Every. Single. Time. Without Exception.

That may be true for models and bodybuilders, but not everyone and not every time.

Let’s take one of the female models who sheds the few pounds she needs to shed for a shoot and look at her years later. Now she’s a 48-year-old mom with three kids. Instead of weighing 118 pounds, she now weighs 154 pounds. She decides she needs to drop back to her 118 pounds for her 30th high school reunion. So she backs off the calories just as she did 30 years before, and she barely loses anything. The ‘Every. Single. Time. Without. Exception.’ doesn’t work the same way it did when she was 20 years old and 118 pounds.

She’s gone through three pregnancies, she’s had huge hormonal changes, she now has has a lot of excess weight she’s carrying around, probably a touch of insulin resistance, and may be peri-menopausal—i.e., she’s not the same person she was three decades earlier.

Three decades earlier she had great metabolic flexibility. As she aged, went through pregnancies, and gained weight, she lost a lot of her metabolic flexibility. When your metabolic flexibility is gone or going, cutting back a little here and there doesn’t do squat. When metabolic flexibility goes, so does the ‘Every. Single. Time. Without. Exception.’ guarantee.

If the same person who could drop five extra pounds in no time at age 20 by cutting calories can’t do it at age 48, then Dr. Feynman’s rule holds. If your theory is that cutting calories works to make you lose weight Every. Single. Time. Without. Exception. doesn’t work in some instances, then the theory is wrong.

Or it needs to be modified. Maybe it is if you are young, healthy, don’t have much weight to lose, and have great metabolic flexibility, then CICO works.

But it certainly doesn’t work in the great majority of people who don’t fit that mold.

According to those of use who believe in the carbohydrate-insulin model (CIM), which includes all of the low-carb docs working today along with Julius Bauer (the father of the theory) back in the 1940s, it is not just the calories that count, but instead, what the body does with those calories. Which is a function of nutrient partitioning.

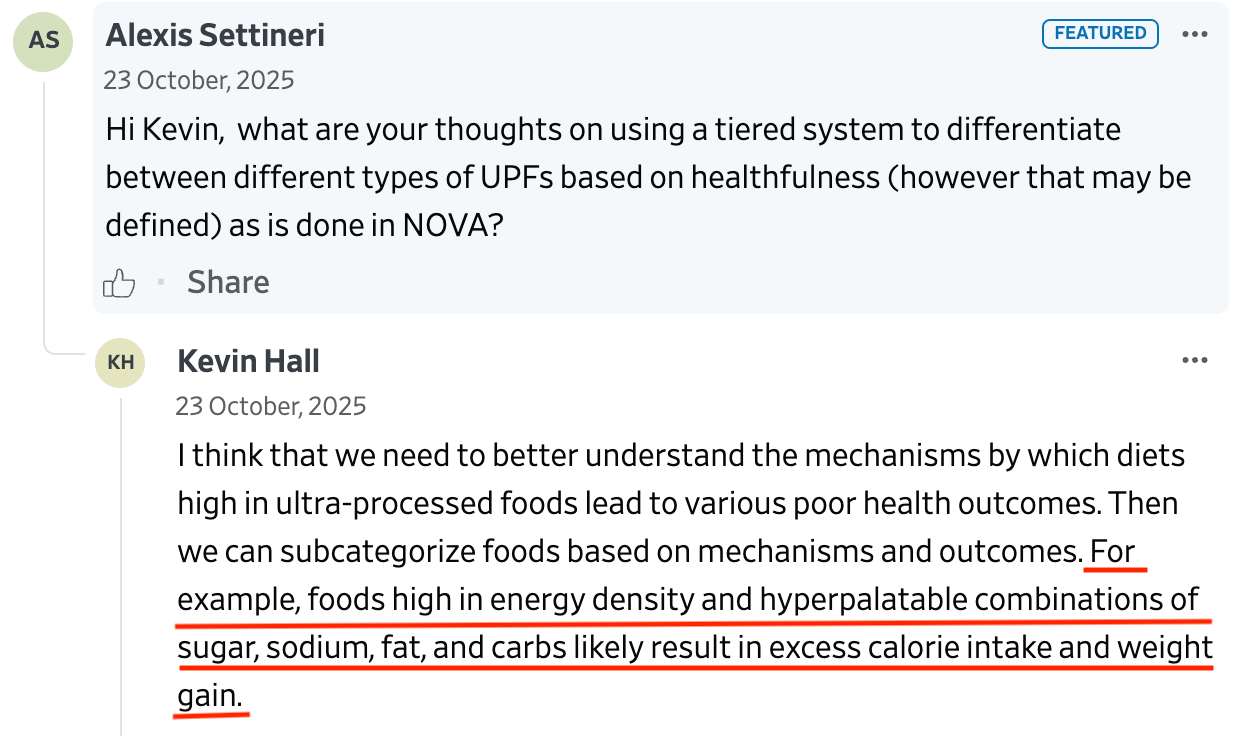

Nutrient partitioning is a much more difficult concept to understand than CICO, which is doubtless why so many have grasped onto the latter. For example, Kevin Hall, formerly of the NIH, who is now answering questions from WSJ readers, and is a major proponent of CICO writes:

In other words, we eat more because we’re confronted with foods high in energy density, etc. CICO to the core.

One of your fellow readers of The Arrow started a Substack not all that long ago. His name is Adam Kosloff. He is a professional writer, and he has been involved with low-carb for decades. His most recent post is on metabolic nutrient partitioning, which is excellent. If nothing else, it demonstrates how complex it is to think about in comparison to CICO.

I’m going to hit one or two high points, but I encourage you to read Adam’s entire post if you want to better understand nutrient partitioning.

He starts off with the story of a couple of researchers named Lois and Theodore Zucker, who worked with rats that got really fat. Zucker rats are a standby now in obesity research.

Like most people today, the Zuckers assumed obesity was a simple case of eating too much. And at first glance, the Zucker rats fit the mold perfectly—they were voracious eaters, outpacing their lean littermates in food intake. Their obesity, it seemed, was a textbook case of calories in, calories out (CICO): they ate too much, so they got fat. Case closed.

But then the researchers did something clever. They restricted the Zucker rats’ diets, feeding them the exact same portions as their lean counterparts. By all logic, the rats should have slimmed down. They did not. Their fat depots refused to shrink.

Intrigued—and possibly in a supervillain-y mood—the researchers dialed up the metabolic torture.

The rats’ food bowls were nearly emptied, leaving them just enough kibble to stave off death. In any normal animal, this level of caloric deprivation generally forces the body to burn its fat stores for survival. That’s (part of) what fat is for—to keep you alive when food is scarce.

But even starvation wasn’t sufficient to unlock the Zuckers’ vast reserves of adipose tissue. Instead, their bodies chose to devour muscle and organs for fuel. Finally, in a grotesque finale, they literally ate their own hearts and died of heart failure.

Yet even in death, their bodies still carried significant excess fat—more than healthy lean rats.

The Zucker rat story above proves CICO wrong. Even when the rats were starved (no calories in), they refused to lose weight.

Adam has a funny, but sad, story near the end. He relates how years ago, he got into an email debate with a physician who was basically all in on CICO. She was well known and “a respected advocate of scientific skepticism and evidence-based medicine.”

He presented his arguments much as he has in his Substack. He asked about Zucker rats. And asked her how CICO could possibly “account for fat accumulation in animals that aren’t overeating?”

She wrote back—and I quote:

“I am not skeptical of calories-in, calories-out because I’ve seen it work for my dog.”

That was her response.

Not a word about the Zucker rats. Not a single attempt to address the data. Just “I put my dog on a diet, and he lost weight.” Yeesh.

Jesus wept.

I really encourage you to read Adam’s Substack (link once more). He ends up with a list of the real questions we should all be asking about why so many people have trouble losing weight.

That’s about it for today. Keep in good cheer, and I’ll be back before you know it.

Please help me out by clicking the Like button, assuming, of course, that you like it.

This newsletter is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end. Really, thanks. If you got something out of it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber if you aren’t yet. I would really appreciate it.

And pass it along to a friend who might be interested.

Finally, don’t forget to take a look at what our kind sponsors have to offer. Dry Farm Wines, HLTH Code, Precision Health Reports, and Jaquish Biomedical.

And don’t forget my newest affiliate sponsor Lumen. Highly recommended to determine whether you’re burning fat or burning carbs.

Reply